EXPOSURE MEASUREMENT

When measuring light, the photographer usually points the photocell of his light meter at the object to be photographed before taking the picture. The measurement is made from a point, from which he intends to take a photo. As we shall see next, this measurement is very far from perfect, and the correct exposure of the photo can be owed not so much to the precision of the light meter, how much huge tolerance of the negative emulsion.

We know the following ways to measure exposure (exposure) photo:

- lighting tables,

— nomogramy,

- sliders,

- memory lighting tables,

- chemical light meters (unused),

- optical light meters (almost unused),

- photoelectric light meters.

Please pay attention to this, that the use of different methods in the same case may produce results that differ significantly from one another: this is due, among other things, to the different emulsion processing methods, because the nature of the development process determines the amount of details extracted on the negative. Some phototechnicians adhere to the old principle of overexposing the negative, others believe, that overexposure leads to a deterioration of image sharpness and increased graininess. However, thanks to the huge tolerance of modern negative emulsions, we will get negatives correctly exposed regardless of this, How will we measure light?.

Emulsion tolerance is its ability to reproduce the image correctly regardless of exposure variations. And so an emulsion with a high tolerance gives a correct image with some underexposure, especially with multiple exposures. Most often, highly sensitive emulsions have a high tolerance.

There are a large number of tables that differ from each other both in terms of the method of calculation, as well as the final result.

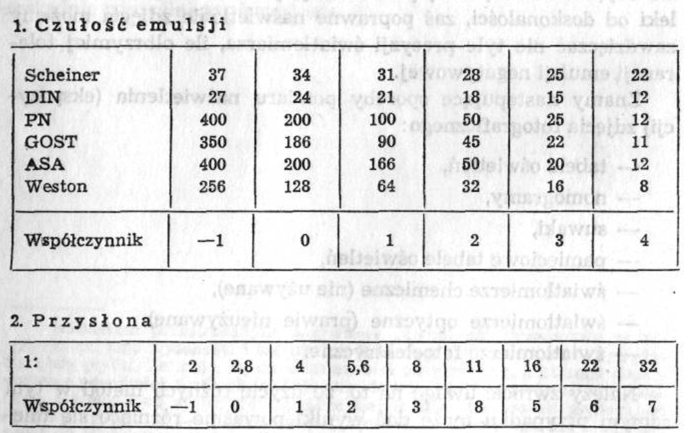

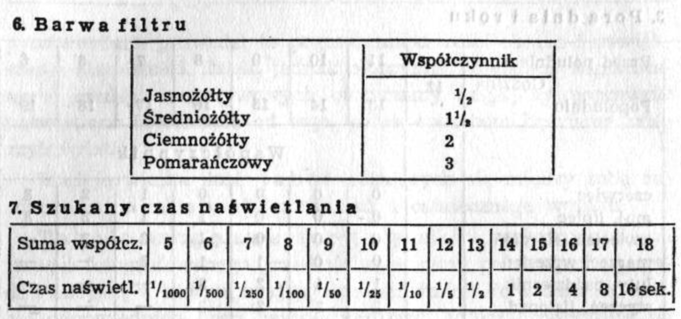

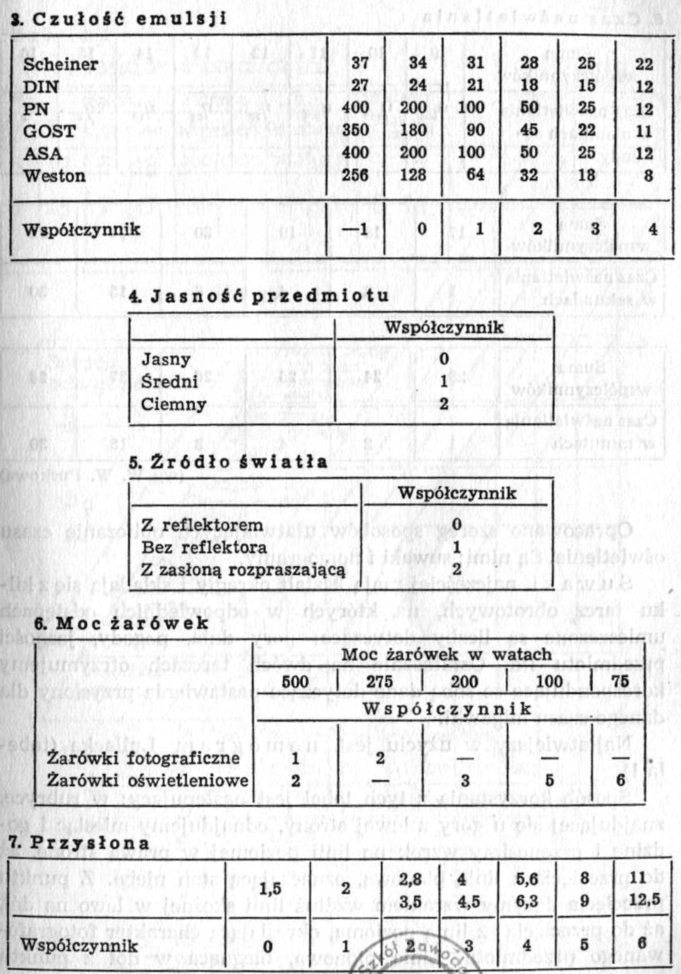

The tables take into account a number of factors affecting the brightness of the photographed object; they are: photo time, weather and place, where the item is located. After adding the appropriate numbers together (coefficients) the photographer reads on a separate table which aperture he should use at a given exposure time.

Auto tabela (very old) for daylight:

Example. On a sensitive emulsion 18 FROM (1) at the aperture 1:8 (3), in May at 18 (e) with a clear sky (0), shooting street scenes (2) we should illuminate: 1 + 3 + 2 + 0 + + 3+2 = 11, what's on the table 7 gives 1/10 sek. (wg T. Cyprian).

Example. On a sensitive emulsion 18 FROM (1) at the aperture 1:8 (3), in May at 18 (e) with a clear sky (0), shooting street scenes (2) we should illuminate: 1 + 3 + 2 + 0 + + 3+2 = 11, what's on the table 7 gives 1/10 sek. (wg T. Cyprian).

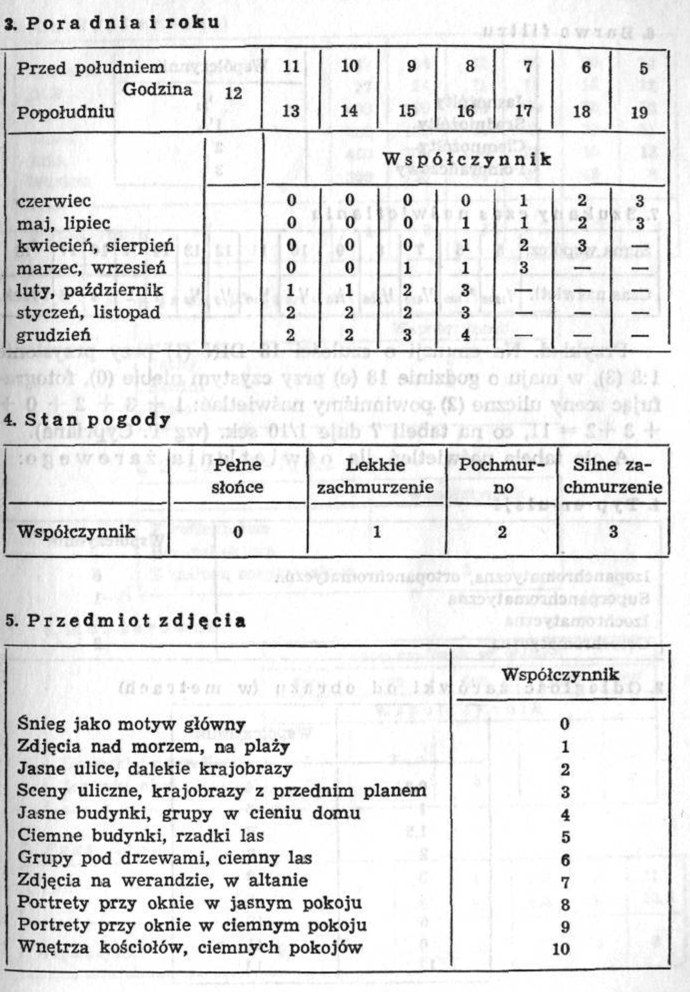

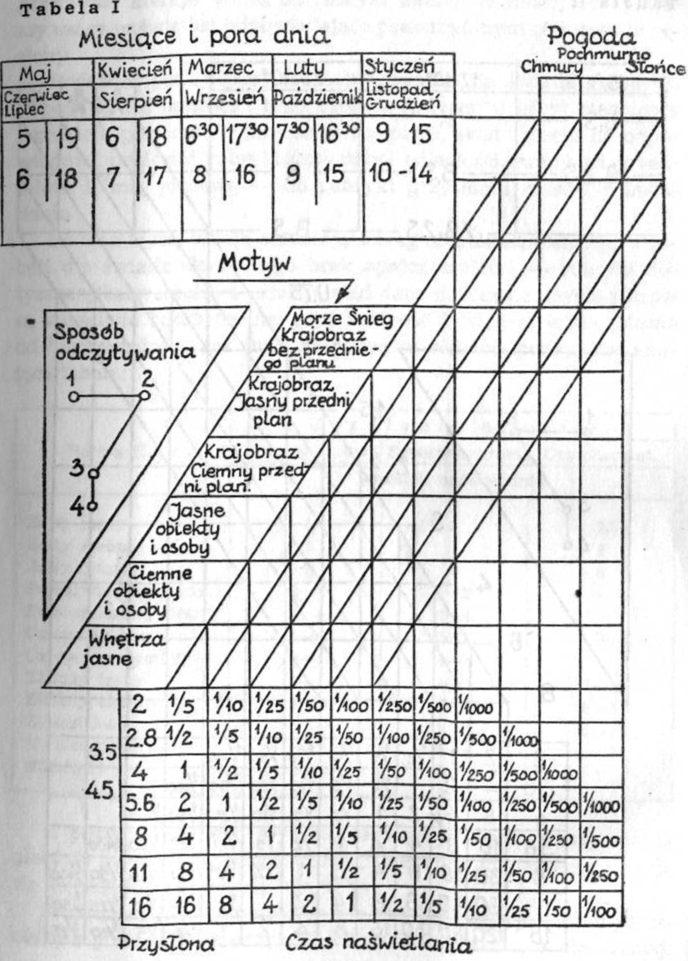

Here is the exposure chart for incandescent lighting:

A number of methods have been developed to facilitate the calculation of lighting time. They are: sliders and nomograms.

Sliders are most often circular in shape and consist of several rotating discs, on which the relevant numbers are placed at appropriate intervals: time of day, weather, object brightness, etc. Finally, on two dials we receive corresponding data on the aperture setting for a given shutter speed.

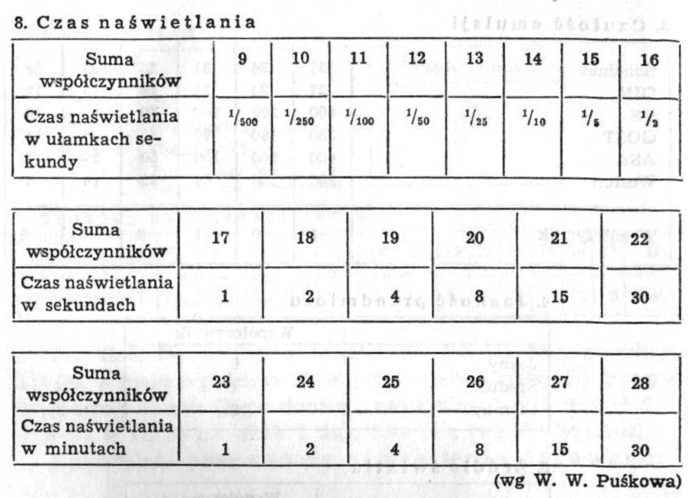

The easiest to use is the Lullack nomogram (table 1).

The way to use these tables is as follows: in the column, located on the top left, we find the month and the hour and move our eyes along the horizontal line to the right, until it intersects the vertical line, signifying the state of heaven. From the intersection point, we follow the diagonal line to the left downwards with our eyes, until it intersects the horizontal line, defining the nature of the photographed object. Vertical line, down from the intersection point, points to the bottom column, in which we read the exposure times corresponding to the individual apertures.

Similarly, we use the nomogram for incandescent light (table 2). From the sensitivity and type of bulb (top left) we run our eyes horizontally to the brightness of the object, from where diagonally to the appropriate horizontal column for the distance of the lamp from the object and the vertical line to the aperture and exposure time column.

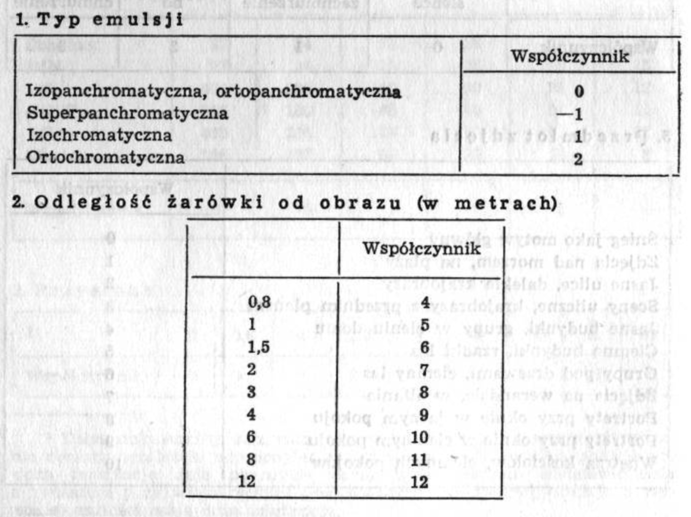

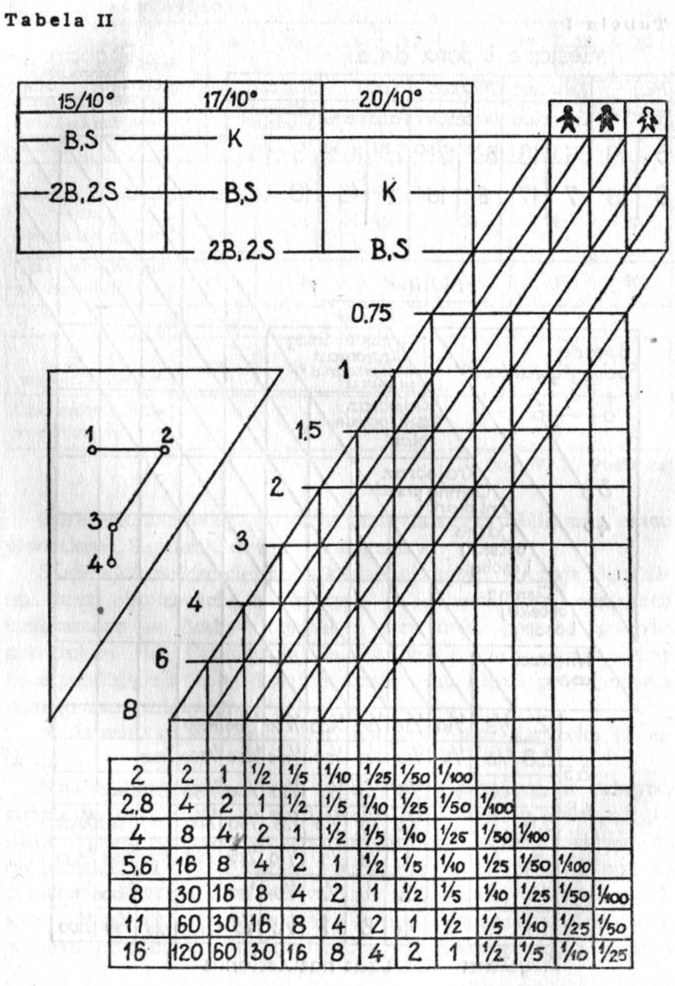

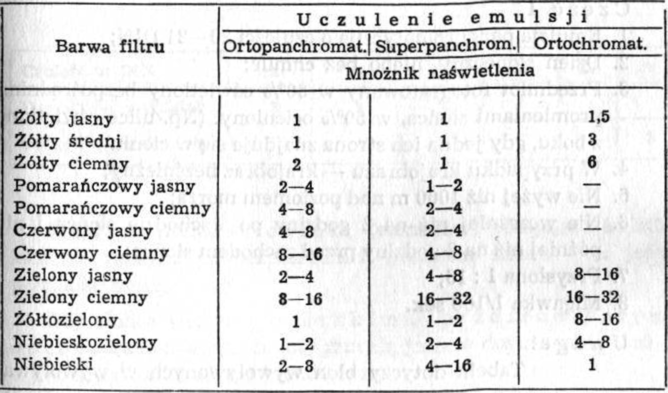

The tables given above have a number of inaccuracies. Np. in the table for sunlight, apart from sensitivity, there is no column concerning the color sensitivity of the emulsion, hence filter usage data is pretty much useless, because the multiplicity of the filter is strictly dependent on the color sensitivity. How big are the differences here, is given in the following table:

It follows from the table above, that orthochromatic emulsions are insensitive to orange and red light (therefore filters in these colors are not applied to them).

On the other hand, the dark yellow filter for superpanchromatic emulsion does not extend the exposure time, and for the emulsion

orthochromatic extends it six times. Meanwhile, the blue filter, no visible effect on orthochromatic emulsions, it can in some cases extend the exposure on orthopanchromatic emulsion up to eight times, and on superpanchromatic even sixteen times.

This must also be taken into account, that the same name filters, produced by different companies, have very different coefficients.